Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Pelvic organ prolapse – with or without urinary incontinence – is common. Although it may not be talked about much, minor degrees of prolapse affect up to 50% of all women who have had a vaginal delivery, while 20% have symptoms that require them to seek care. One in 9 women will have surgery for prolapse or incontinence in her lifetime.

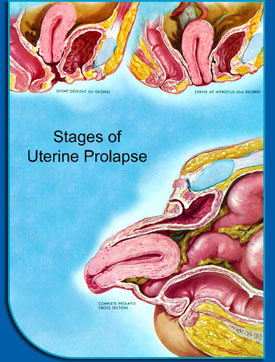

Normally, a woman's pelvic organs are supported by the muscles of the pelvis. Her uterus, vagina, bladder and rectum are held over the muscles that provide support to keep the organs in place. If the muscles or supportive connective tissue is weak, damaged or stretched, any or all of the organs can begin to slip downward into the vagina. Occasionally, if left untreated, the organs can protrude outside of the vagina or body.

Early symptoms can include a feeling of pressure at the end of the day, feeling like one is sitting on something all the time, feeling something protruding when wiping after voiding, an altered urinary stream or difficulty initiating voiding. Sometimes a woman will experience altered sensation with intercourse or feel like her partner is hitting something. Women with prolapse may also experience bladder or bowel symptoms, such as difficulty controlling urges or incontinence with coughing, sneezing, exercising and other activities.

Causes of prolapse or pelvic floor disorders

Although the exact cause of prolapse is not known, vaginal childbirth is the biggest risk factor. Certainly, the birth weight and number of children a woman has can increase the risk, but even a single small child can lead to prolapse or urinary incontinence. It's likely related to muscle and nerve damage that can occur with vaginal delivery, but not every woman who delivers her child vaginally will get prolapse, and not every woman with prolapse has delivered a child vaginally. Even a cesarean section does not eliminate the risk of prolapse or incontinence. Genetics also contributes to risk of prolapse, as pelvic floor disorders are more common among siblings with prolapse or incontinence. Other factors that can increase a woman's risk are anything that puts chronic strain or stress on the pelvic organs (chronic cough, obesity, constipation or repetitive heavy lifting).

Treatments

If a patient is not bothered by prolapse, she may not need any treatment at all. In general, treating prolapse is about quality of life. Patients should be reassured that this is common and, except in rare situations, can usually be monitored without treatment. However, if patients are bothered by prolapse or incontinence, there are many treatments available that can help them get back to a normal life. There is no reason to live with prolapse or incontinence if it bothers you or affects your quality of life.

Nonsurgical treatments

Kegel exercises or physical therapy can help strengthen the pelvic muscles. This is helpful with urinary incontinence and may delay the development of prolapse. However, it is unlikely that exercises alone will repair significant vaginal prolapse. Pessaries are removable rubber or silicone devices that can be placed in the vagina to hold the organs in place. Once appropriately fitted, a pessary can be removed and cleaned on a regular basis by the patient for as long as she would like. Pessaries often work well, but the prolapse will likely return if pessary use is stopped. Therefore, we recommend pessaries for young woman who may want to have more children, women who have a medical condition that makes surgery inadvisable, or for women who'd like to postpone surgery for some period of time – perhaps to take care of an ill family member or when it may be more convenient for her schedule.

Surgical options

There are several ways to surgically treat prolapse, and there is no one right answer for all patients. We suggest a consultation with a fellowship-trained urogynecologist to determine which option is best for each patient. Below is a brief explanation of the different types of surgical repairs that may be considered.

Vaginal repairs

Traditional vaginal repairs have been used for several decades. These repairs are used for bladder prolapse, cystocele, rectocele, enterocele, uterine prolapse and vaginal prolapse. These repairs are very common and are performed by many gynecologists. They are called anterior or posterior repair, colporrhaphy, uterosacral or sacrospinous vault suspensions. They are the simplest to perform and have the advantage of being performed through an entirely vaginal approach. That means that they don't generally require a long hospital stay and are relatively well tolerated. Patients usually stay 1 to 3 days in the hospital after surgery. The surgeon treats the prolapse using the patient's own tissue to repair the connective tissue attachments. Although this may be a good option for some patients, this approach has the highest risk for recurrent prolapse. According to the literature, 20 to 40% of patients may experience return of their prolapse in the future. It should be noted that although this is a seemingly high recurrence rate, many of those patients will NOT have symptoms or need repeat surgery.

Abdominal repairs

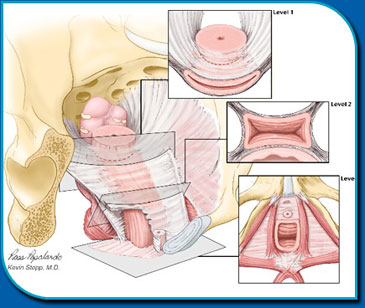

Another option for prolapse repair is called abdominal sacral colpopexy. This procedure has been performed for more than 20 years. It is a very good operation for uterine or vaginal prolapse. In fact, many consider it the "gold standard." The success rate is well above 90% for at least 20 years. This success rate is, at least in part, because the repairs are performed using a permanent surgical mesh implant.

Many urogynecologists prefer this procedure when vaginal surgery fails or recurs. It is more difficult and is generally only performed by specialists. The vagina is re-suspended to strong ligaments in the pelvis by the mesh. Since the repair doesn't rely on the patient's own tissue, the repair has a much better chance of lasting 20, 30 years or more. Other defects can be treated at the same time with procedures that repair specific defects, such as paravaginal defect repair and enterocele repair.

The disadvantage is that with most surgeons, this is usually performed through a large abdominal incision. This is much more invasive than vaginal repairs. Patients often spend 2 to 4 days in the hospital.

Laparoscopic repairs

Relatively recently, surgeons skilled in advanced laparoscopy have perfected laparoscopic sacral colpopexy. With this approach, patients can receive the "gold standard" procedure with the best success rates – but in a minimally invasive procedure. A small camera is inserted through the umbilicus (belly-button). Additional thin instruments are inserted through a few small incisions less than ½ inch long. The remainder of the surgery is completed like the well-studied abdominal approach.

Laparoscopic sacral colpopexy is difficult and requires several specific skills to complete. With additional training, surgeons can perform the entire case by laparoscopy. In some cases, surgeons may use robotic assistance to overcome some of the more difficult aspects of this complex laparoscopic case. Many patients are able to go home the same day of surgery or after observation overnight. Some patients may be a candidate for the newest type of laparoscopy called laparo-endoscopic single site surgery (LESS), using only a single tiny incision in the umbilicus to complete the entire prolapse repair.

Vaginal mesh repairs

When comparing traditional vaginal repairs with sacral colpopexy, many surgeons feel that the improved success rates of sacral colpopexy are due to its use of a permanent mesh material, rather than relying on the patient's own weakened tissue. In an effort to improve the results of traditional vaginal repairs and avoid the more invasive open abdominal approach, surgeons began to explore placing mesh vaginally to repair prolapse. Surgeons in Europe were the first to develop some of these techniques and it has been performed in the United States since 2001. (Kevin Stepp, MD trained with one of the original developers in France.)

During the procedure, a mesh implant is placed through vaginal incisions using specifically designed instruments. The early results of published reports suggest vaginal mesh procedures have the potential to improve the anatomic success rates for prolapse repair. Other advantages for these procedures include minimal pain, an overnight hospital stay and short procedure time. Longer surgeries place patients at higher risk of complications, particularly patients who are over 70 years old. Potential disadvantages include lack of long-term research, possible pain with sexual activity or problems related to mesh healing. We generally do not perform this procedure on patients who are or plan to be sexually active.

Pelvic reconstructive surgery

Our urogynecologists specialize in rebuilding and restoring the vagina and pelvic anatomy to its normal state. Whether patients have experienced trauma during childbirth, episiotomy or as a result of complications from prior surgery, we can help restore the normal appearance of supportive and functional structures of the pelvis and vagina. Our approach is to address the entire pelvis from the deeper supportive ligaments to the outer structures also responsible for good support and function.

Our Providers

If you need care, these are some of the specialists you might see. Use the filters to get to know the team.